Birth of A City Almost twenty years to the day after fighting the British at the Battle of Bunker Hill, Colonel Seth Reed dragged his small sailboat up onto the sands of Presqu’ Isle. His wife and two children had bravely accompanied him to this frontier - a place so removed from the cultured cities of Europe and the burgeoning settlements of America’s eastern states that it could rightly be called the edge of the known world.

That evening the family slept by a small fire, no doubt in fear that hostile Indians could erupt from the forest at any moment. Ironically just across the bay on a bluff by what would later become Parade Street in Erie, Pennsylvania, a few American soldiers looked out and, seeing the fire, concluded that some Indians must be hunkering down on the peninsula readying for a brutal attack. The soldiers rowed out in the morning to investigate, and one can easily guess how relieved both parties must have been to discover each other.

Thus arrived the first “official” settlers to Erie, Pa. on July 1, 1795.

In many ways, though, these first settlers were simply playing their role in a story that had begun hundreds of years earlier....

|

A Wilderness in Dispute Erie is, of course, named for the Eriez Indians who lived along the southern shore of the lake that now bears their name and utilized the immediate locale as favored hunting and fishing grounds. Little is known of the Eriez, since they had no written language and they had only the briefest encounters with Europeans. In 1615, Joseph LeCaron lead a group of French missionaries into the area but met with little success in converting the natives to the Catholic faith. Eleven years later the Jesuits tried their luck by sending Father D’Allyon to visit the Eriez villages, but he could do no better. With the exception of the scant written records of these missionaries, the little we know of the Eriez is through archeological excavation and oral history.

Tradition holds that this indigenous tribe was led by Queen Yagowanea, a North American Solomon of sorts, who was renowned far and wide for her wisdom and fairness. When disputes arose amongst the Eriez- or even between other tribes - she was called upon to mediate and dispense her wisdom. Her people were fierce warriors, but preferred instead to cultivate their status as a “neutral nation”, acting as a buffer between the Iroquois alliance to the east and the Wyandots and Hurons to the west. Legend has it that when Yagowanea took sides in a dispute involving the murder of a Mississaguan Indian, the Seneca Nation became so enraged that they took up arms against the Eriez, and eventually exterminated the noble tribe. While the historical veracity of this tale is questioned by modern scholars, it is undoubtedly true that the Senecas had virtually displaced the Eriez by 1654. The Senecas, however, did not occupy the land though they claimed title to it. In reality, the land reverted to wilderness for the next one hundred years, slowly erasing footprints and village-sites of the previous inhabitants.

|

Two World Powers Collide At Presqu’ Isle The strategic geographical importance of Northwestern Pennsylvania was recognized early on by both the French Canadians and the British colonists. By the 1750’s the two great European powers were embroiled in a virtual world war, and one small but significant facet of the conflict centered around land claims to the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River Valley. During the previous century, a myriad of French explorers had mapped these lands and claimed them for France. Yet the official charters that created the British colonies on the Eastern seaboard typically used language like “from sea to sea”, giving England claim to these very same lands. The wilderness of northwestern Pennsylvania would figure prominently in the resolution of this inherent dispute.

The French acted first, in 1753, when Canadian Governor Duquesne dispatched an expedition under Sieur de Marin with explicit instructions to build three forts to protect the portage between Lake Erie and the Ohio River drainage. Previous expeditions had shown that the French could proceed up the St. Lawrence and into the Great Lakes; and that by “portaging” (carrying their canoes and equipment over land) from what is now Barcelona, N.Y. to Lake Chautauqua they could access a waterway that would eventually drain into the Mississippi. This portage was literally the keystone between the St. Lawrence and the Mississippi- an all important link in the chain between the French cities of Montreal and New Orleans. Fortification of the route was imperative.

Just as Marin arrived at the site of the original portage, he received a communication from the Governor urging him to travel further down the lake shore to a site that an unnamed “famous voyageur” had assured him would be an ideal harbor “where there is the best hunting, fishing, fertile land, immense meadows to feed and raise cattle, where Indian corn grows with unequalled abundance so that it need only be sown.” That place, of course, was Presqu’ Isle. Marin proceeded as directed and by August 1753 he could report to the Governor that a fort at Presqu’ Isle was completed, that a road to Lake LeBoeuf (Waterford) had been constructed, and that a fort at Le Boeuf was under way. Just as Marin arrived at the site of the original portage, he received a communication from the Governor urging him to travel further down the lake shore to a site that an unnamed “famous voyageur” had assured him would be an ideal harbor “where there is the best hunting, fishing, fertile land, immense meadows to feed and raise cattle, where Indian corn grows with unequalled abundance so that it need only be sown.” That place, of course, was Presqu’ Isle. Marin proceeded as directed and by August 1753 he could report to the Governor that a fort at Presqu’ Isle was completed, that a road to Lake LeBoeuf (Waterford) had been constructed, and that a fort at Le Boeuf was under way.

The Governor of Virginia, Robert Dinwiddie, heard about the French expedition and, seeing it as an intrusion into lands rightfully belonging to England, resolved to send a formal message to the interlopers to cease and desist. He chose for his official messenger a 21 year old surveyor named George Washington. Washington set out on Halloween with a small group of men and battled through the early mountain snowstorms to arrive at Fort LeBoeuf on December 11th. He was well received by the commander of the fort, and he delivered Dinwiddie’s letter. The French politely thanked him but issued a written response indicating that they intended to fulfill their orders and stay. When Washington returned to Virginia, he published his journals of the account of this, his first public commission. The journals were widely distributed throughout England and the Colonies, thrusting Washington into the public consciousness. The rest, as they say, is history.

As promised, the British spent the next 6 years (1753-59), endeavoring to attack and ultimately seize many of the forts constructed by the French. In 1759 the French were forced to abandon Fort Presqu’ Isle, burning it to the ground as they left. The following year the British rebuilt the fort on the same site, seeming to claim this new frontier as their own. But they had not reckoned on the Indians.

|

The Indians Retaliate  In 1763, the persuasive leader of the Ottawa Nation, Chief Pontiac, masterfully assembled an enormous coalition of Indian tribes including the Six Nations of the Iroquois. In one sweeping blitzkrieg, they simultaneously attacked British forts throughout the Great Lakes and the Ohio Valley. On June 15, Presqu’ Isle fell, and LeBoeuf followed just 2 days later. The immediate area reverted to Indian control. In 1763, the persuasive leader of the Ottawa Nation, Chief Pontiac, masterfully assembled an enormous coalition of Indian tribes including the Six Nations of the Iroquois. In one sweeping blitzkrieg, they simultaneously attacked British forts throughout the Great Lakes and the Ohio Valley. On June 15, Presqu’ Isle fell, and LeBoeuf followed just 2 days later. The immediate area reverted to Indian control.

The British eventually quelled the uprising and retook many of the forts that had fallen; but troubles with the insurgent colonists on the Eastern seaboard turned British attentions away from rebuilding anything in the region of Presque Isle. For the next three decades while the East was enveloped in outrage, rebellion and ultimately war, the area was strangely quiet again and devoid of any European settlement.

|

Setting the Stage for Settlement After the necessary distractions of the Revolutionary War, Americans again began looking to the West to satiate their hunger for land. Both the U.S. government and the Pennsylvania legislature sought to encourage this expansion, but the omnipresent specter of Anglo-American settlers being scalped by hostile natives was keeping most folks on the Eastern side of the Appalachians. The various governments sought to combat this in three distinct ways. First of all, they recognized that they needed to use the military to make the area secure for settlement. Secondly, they needed to begin the process of surveying and distributing land and physically laying out cities. Finally, they reasoned, actual settlers would begin the process of moving westward, settling land, and putting down roots.The British eventually quelled the uprising and retook many of the forts that had fallen; but troubles with the insurgent colonists on the Eastern seaboard turned British attentions away from rebuilding anything in the region of Presque Isle. For the next three decades while the East was enveloped in outrage, rebellion and ultimately war, the area was strangely quiet again and devoid of any European settlement.

|

Mad Anthony Wayne  Historians today debate the degree to which reports of Indian raids on frontier settlements were exaggerated in frequency and brutality. However, one can safely say that the perception of danger was widespread, and in a very real sense was suppressing the willingness of families to move westward. At the same time, the nascent sense of what would later be called “manifest destiny” was already setting up an inevitable conflict with the Indians who simply wanted to keep their homelands. Through the prism of history, we now universally regard this as a tragedy; at the time, though, it was equally universally regarded as a threat. Historians today debate the degree to which reports of Indian raids on frontier settlements were exaggerated in frequency and brutality. However, one can safely say that the perception of danger was widespread, and in a very real sense was suppressing the willingness of families to move westward. At the same time, the nascent sense of what would later be called “manifest destiny” was already setting up an inevitable conflict with the Indians who simply wanted to keep their homelands. Through the prism of history, we now universally regard this as a tragedy; at the time, though, it was equally universally regarded as a threat.

To combat the threat, the newly created Federal Government enlisted the aid of General “Mad” Anthony Wayne, a Revolutionary sidekick to George Washington, to spearhead an ultimately successful series of military expeditions against the Northwest Indians. The campaign, which began in 1792, was fought throughout the Ohio Valley, culminating in the Indians’ defeat at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in August of 1794. The treaty of Greenville, signed the following year, ceded vast lands north of the Ohio River to the United States. Mad Anthony had finally made the area safe for settlement.

General Wayne left an even more indelible mark on Erie, Pennsylvania when he chanced to die at Fort Presque Isle on December 15, 1796 while quartered there. As was his dying request, he was buried beneath the flagstaff on a knoll overlooking Erie’s bay. Thirteen years later, his son decided to move the body to the family burial plot in Radnor, PA. The body was exhumed and found to be in a remarkable state of preservation- making it much too heavy (and ripe) to withstand the cart travel across the state. In a gruesome moment that would become the stuff of legends, it was decided to boil the body in a great vat to render the flesh from the bones. The bones were brought to Radnor; the flesh was reinterred beneath the flagstaff; and the debate continues to this day as to where resides the ghost of Mad Anthony Wayne.

|

The Erie Triangle  During the time that Wayne was fighting the Indians, the Pennsylvania legislature had begun to prime the pump for settlement by setting up a “Donation District” in northwestern PA that would be used to pay Revolutionary soldiers for their service with grants of land. In reality though, land speculators, including the newly formed Pennsylvania Population Company, wasted no time in gobbling up these parcels at bargain prices - temporarily thwarting the government’s goal of populating this frontier with able bodied veterans. During the time that Wayne was fighting the Indians, the Pennsylvania legislature had begun to prime the pump for settlement by setting up a “Donation District” in northwestern PA that would be used to pay Revolutionary soldiers for their service with grants of land. In reality though, land speculators, including the newly formed Pennsylvania Population Company, wasted no time in gobbling up these parcels at bargain prices - temporarily thwarting the government’s goal of populating this frontier with able bodied veterans.

It was always obvious to the Pennsylvania legislature that it would be an enormous strategic benefit to have a port on the Great Lakes. The problem was that New York, Connecticut, and Massachusetts all claimed what was called the “Erie Triangle”. Ultimately, the Federal Government interceded, the various states withdrew their claims to the land, and in 1792 the State of Pennsylvania bought the land for $151,640.25. They immediately appointed Thomas Rees to go there and survey the land. For two years he tried to fulfill his commission, but was repeatedly repelled by tomahawk wielding Indians.

By 1794, as Mad Anthony Wayne was busy defeating the Indians at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, Rees was joined by fellow surveyors Andrew Ellicott and General William Irvine under the protection of the Allegheny Brigade of State Militia. The following year, Rees was finally able to begin to survey and sell land while Ellicott and Irvine began to lay out the town of Erie.To combat the threat, the newly created Federal Government enlisted the aid of General “Mad” Anthony Wayne, a Revolutionary sidekick to George Washington, to spearhead an ultimately successful series of military expeditions against the Northwest Indians. The campaign, which began in 1792, was fought throughout the Ohio Valley, culminating in the Indians’ defeat at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in August of 1794. The treaty of Greenville, signed the following year, ceded vast lands north of the Ohio River to the United States. Mad Anthony had finally made the area safe for settlement.

General Wayne left an even more indelible mark on Erie, Pennsylvania when he chanced to die at Fort Presque Isle on December 15, 1796 while quartered there. As was his dying request, he was buried beneath the flagstaff on a knoll overlooking Erie’s bay. Thirteen years later, his son decided to move the body to the family burial plot in Radnor, PA. The body was exhumed and found to be in a remarkable state of preservation- making it much too heavy (and ripe) to withstand the cart travel across the state. In a gruesome moment that would become the stuff of legends, it was decided to boil the body in a great vat to render the flesh from the bones. The bones were brought to Radnor; the flesh was reinterred beneath the flagstaff; and the debate continues to this day as to where resides the ghost of Mad Anthony Wayne.

|

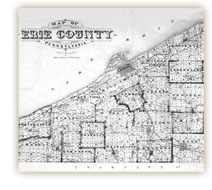

Laying Out A Town An Act of the PA legislature provided for Erie to be laid out in three districts, each roughly 1 mile square. The districts ran from the bay front to 12th Street, with the first district between Parade and Chestnut, the second between Chestnut and Cranberry, and the third between Cranberry and West Streets. Each district was to include a park for public use, which we would recognize today as Perry Square, Gridley Park, and Frontier Park. The east-west roads were to be numbered and twenty rods (330 ft) apart. The north-south roads to the west of State Street would be named after trees. Those to the east would be named after nationalities.

Land was reserved on the Peninsula and at the harbor front for the Federal Government to erect forts and construct harbor facilities. The remaining land was surveyed in lots no larger than 1/3 acre, with “outlots” of up to 5 acres in the area between 12th and 26th Streets.It was always obvious to the Pennsylvania legislature that it would be an enormous strategic benefit to have a port on the Great Lakes. The problem was that New York, Connecticut, and Massachusetts all claimed what was called the “Erie Triangle”. Ultimately, the Federal Government interceded, the various states withdrew their claims to the land, and in 1792 the State of Pennsylvania bought the land for $151,640.25. They immediately appointed Thomas Rees to go there and survey the land. For two years he tried to fulfill his commission, but was repeatedly repelled by tomahawk wielding Indians.

By 1794, as Mad Anthony Wayne was busy defeating the Indians at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, Rees was joined by fellow surveyors Andrew Ellicott and General William Irvine under the protection of the Allegheny Brigade of State Militia. The following year, Rees was finally able to begin to survey and sell land while Ellicott and Irvine began to lay out the town of Erie.To combat the threat, the newly created Federal Government enlisted the aid of General “Mad” Anthony Wayne, a Revolutionary sidekick to George Washington, to spearhead an ultimately successful series of military expeditions against the Northwest Indians. The campaign, which began in 1792, was fought throughout the Ohio Valley, culminating in the Indians’ defeat at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in August of 1794. The treaty of Greenville, signed the following year, ceded vast lands north of the Ohio River to the United States. Mad Anthony had finally made the area safe for settlement.

General Wayne left an even more indelible mark on Erie, Pennsylvania when he chanced to die at Fort Presque Isle on December 15, 1796 while quartered there. As was his dying request, he was buried beneath the flagstaff on a knoll overlooking Erie’s bay. Thirteen years later, his son decided to move the body to the family burial plot in Radnor, PA. The body was exhumed and found to be in a remarkable state of preservation- making it much too heavy (and ripe) to withstand the cart travel across the state. In a gruesome moment that would become the stuff of legends, it was decided to boil the body in a great vat to render the flesh from the bones. The bones were brought to Radnor; the flesh was reinterred beneath the flagstaff; and the debate continues to this day as to where resides the ghost of Mad Anthony Wayne.

|

The Settlers Arrive  Like a trickle, and then a tide, hardy pioneers began to cross the mountains and make their way to this wilderness outpost. The first to “officially” put down roots were Seth Reed with his wife and two children. Another early settler was surveyor Rees, who so fell in love with the place that he opted to stay. But it was his successor as agent for the Pennsylvania Population Company, Judah Colt, who was most instrumental in turning Erie into a true settlement. He surveyed and sold land, built roads, and set up a thriving provisioning business, selling everything from muskets to seed corn. Like a trickle, and then a tide, hardy pioneers began to cross the mountains and make their way to this wilderness outpost. The first to “officially” put down roots were Seth Reed with his wife and two children. Another early settler was surveyor Rees, who so fell in love with the place that he opted to stay. But it was his successor as agent for the Pennsylvania Population Company, Judah Colt, who was most instrumental in turning Erie into a true settlement. He surveyed and sold land, built roads, and set up a thriving provisioning business, selling everything from muskets to seed corn.

Settlers continued to come, secure in the promise that with an ax, a horse, and some hard work they could cash in on the dream of real land wealth in this Western frontier. By the dawn of the 19th century there were 81 souls living in Erie, ready to capitalize on the town’s location as a safe harbor and a critical point on the portage between the Great Lakes and the Ohio River Valley.

|

The Work of a Town Early on it was recognized that Erie’s position between the Ohio River drainage and the Great Lakes would make it an essential shipping and transportation center. The first trade to be economically significant was the salt trade. Salt, important enough to be considered the veritable currency of the day, was delivered in barrels by small boats coming down Lake Erie from Buffalo. At Erie, they were offloaded by teamsters who began the arduous task of hauling them to Waterford. The road to Waterford was little better than the footpath that had been constructed by French troops in 1753, and the teamsters’ ox-driven carts were often hopelessly bogged down in mud. The portage typically took four days to travel the 15 mile road.

From Waterford, the salt continued down the Allegheny to Pittsburgh and points along the Ohio. The teamsters often returned to Erie laden with beef, pork, whiskey, flour, and grain headed for the Great Lakes communities.

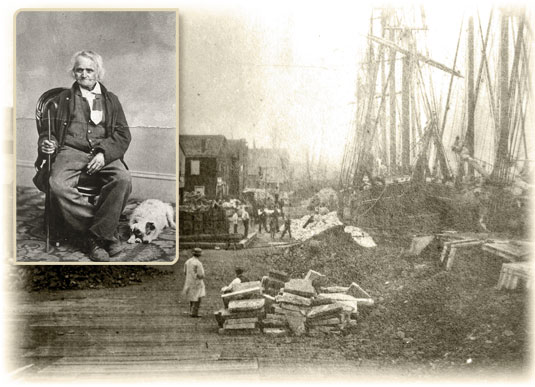

The salt trade sprouted many additional industries, including shipbuilding. The first commercial vessel to be built in Erie was the Washington, constructed near Four-Mile Creek and launched in 1798. The following year, Rufus Reed (the son of the first-settler and tavern owner Seth Reed) built the Good Intent - a ship that destined to sink 7 years later, but not before launching Reed into a shipping empire that would last well into the next century while making him fabulously wealthy.

Erie was not just a way station between other cities, though, and in fact many homegrown industries sprung up to become the town’s first exporters. One of the first was the sawmill built by Thomas Foster. In short order, streams throughout Erie County were powering sawmills that helped to harvest old-growth timber to be supplied to the ship-builders of the Great Lakes. Much of the lumber was also used to build the houses of the burgeoning population of Erie.

The vast majority of early settlers were subsistence farmers and homesteaders who eked out a living from the ground. Like the Eriez Indians a century earlier, these farmers found the land ideally suited for growing corn and grains - and in many instances the flour from these grains was exported from Erie County.

Support industries fared extremely well during this era, and by 1810 the young town was populated with 400 stalwarts including blacksmiths, carpenters, brickmakers, tavernkeepers and provisioners.

|

The Age of Steam The War of 1812 brought a rowdy bunch of soldiers, sailors and shipbuilders to Erie to assist in the construction of Admiral Perry’s fleet. They brought to Erie a cosmopolitan feel - with sailors hailing from many-a-port’o’call including a large number of freed slaves. Their expert work in constructing a fleet and in defeating the British Navy helped put little Erie on the map as a leading shipbuilding center. In fact, Erie was so widely regarded as the gateway to the west that the famous French dignitary Lafayette visited the town of 1000 people in 1825.

In 1826, Erie led the way into to Age of Steam by launching the William Penn, a massive 200 ton steamboat to ply the waters of Lake Erie on behalf of Rufus Reed’s “Lake Erie Steamboat Line”. Reed’s company would become known throughout the Great Lakes as one of the foremost shipping lines.

At the time, Erie did not have sufficient harbor facilities to support the greater size and demands of steamships. The city government on several occasions endeavored to begin construction of a “public dock”, but the plans never came to fruition. Reed took matters into his own hands and constructed a private shipping dock at the foot of Sassafras. For years, all ships coming into the bay were required to come to this dock.

In 1833, Hinckley, Jarvis, and Company constructed the first foundry in Erie, smelting iron ore for use regionally. For the next century, Erie would be at the forefront of the iron and steel industry, manufacturing stoves, furnaces, cooking implements, and machinery. Not surprisingly, the iron industry met the shipping industry early on in Erie when the USS Michigan (later named the Wolverine) was constructed in 1843 - making it the first iron hull on the Great Lakes.

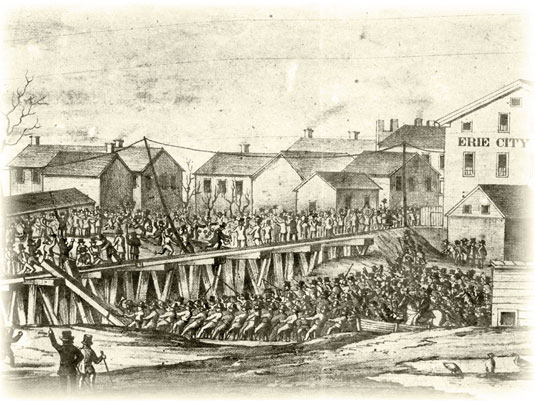

Twenty years before the onset of the Civil War, an all-important political rally held in Erie helped to cement the city’s reputation as a foundry-town. As Democratic President Martin Van Buren squared off against Whig challenger William Henry Harrison, competing rallies were scheduled in Erie. Supporters came from far and wide for the Frontier Convention, with an astounding 80,000 visitors to the city of less than 3500 people. The Presque Isle Foundry took advantage of the large crowds to showcase the iron plows and stoves that they were manufacturing - and the visitors eagerly bought every unit and placed orders for new merchandise. Harrison eventually won the election, o?nly to die quickly of pneumonia contracted at his inauguration. But his vice-president and successor, John Tyler, made sure to reward Erie by giving Presque Isle Foundry a massive government contract to manufacture heavy artillery shot.

|

THE AGE OF CANALS  In 1825, New York State completed the Erie Canal (which did not come to Erie, PA) making it possible to travel from Buffalo to Albany entirely by water. Pennsylvanians looking north readily latched onto the idea of duplicating the feat by connecting Harrisburg to Pittsburgh, and ultimately to Erie, with a canal system. The project was begun immediately, but by 1839 had stalled outside of New Castle. In 1825, New York State completed the Erie Canal (which did not come to Erie, PA) making it possible to travel from Buffalo to Albany entirely by water. Pennsylvanians looking north readily latched onto the idea of duplicating the feat by connecting Harrisburg to Pittsburgh, and ultimately to Erie, with a canal system. The project was begun immediately, but by 1839 had stalled outside of New Castle.

The start of the construction on the canal did, however, light a fire under Erie’s government to begin construction of a public dock. They reasoned correctly that the increase in boat traffic would require world class facilities to accommodate trade. In 1833, carpenter John Justice was hired by the town to construct a dock, which ended up being a 1500 foot extension of State Street to a water depth of 12 feet. The dock, dubbed “Steamship Landing” included seawalls from the Reed Dock at the foot of Sassafras over to the French Street landing.

With or without the canal, the dock had an immediate effect on commerce in the city, and steamships along the Great Lakes made the harbor a regular stop on their routes. By 1842, the state had all but abandoned the idea of completing the canal system. Wealthy Erieites, including the Reed family, agreed to complete the canal in exchange for ownership of the already-constructed sections. The state readily conceded, and the “Erie Extension” was completed by 1844. On a cold December day of that year, the Queen of the West arrived with much fanfare, becoming the first canal boat to complete the journey to the foot of Sassafras.

The optimism of that December day was quickly supplanted, however, by the emerging reality that the future of transportation lay not in canals, but in the mighty railroads. The state had spent millions of dollars and two decades completing the canal, but by the 1850’s the system was already in disrepair and was auctioned off to the Pennsylvania Railroad Company.

|

Fishing From the time of the earliest settlement in Erie, fishing was an important source of sustenance and commerce. Expert Native American fishermen plied the waters of Presque?Isle Bay and Lake Erie with hook-and-line, angling for the bountiful herring and whitefish that they eagerly traded with the first settlers.

Historians trace the beginnings of commercial fishing in Erie to the turn of the 19th century when a free black man named McKinney learned the techniques of the Indians and became the young town’s first fishmonger, selling his catch from a pier on the bayfront. When he died in 1815 (he poetically choked on a fishbone) his son-in-law “Bass” Fleming took over the business and expanded.

In the period between 1830 and 1850, several local fishermen began to set out nets, quietly becoming the first large scale commercial fishermen in Erie. Their hauls were reportedly spectacular, with large whitefish and salmon filling the nets. Fishing from small cat-rigged sailboats, they occasionally pulled in a monster sturgeon, straining both the sails and the fragile nets.

The lake sturgeon, a fish reaching an astonishing length of six feet, was originally thought to be a nuisance fish. In short order, though, fishermen began to extract the roe which could be salted and shipped to Europe and sold as the delicacy caviar. Thousands of these magnificent fish were thus processed, and since their flesh was considered to be inedible, their huge carcasses were buried on the peninsula. It wasn’t until several decades later that tastes changed sufficiently to create a market for smoked sturgeon, thereby ensuring the species eventual decline.

By the turn of the century, there were more than 50 fishing boats operating from Pennsylvania’s shoreline, bringing in about 15 million pounds of fish each year. Erie was widely considered to be the fresh-water fishing capital of the world with over 500 men directly employed in the enterprise and perhaps twice as many in spin-off industries like boatbuilding, shipping, and outfitting.

A visitor to the busy docks at that time could have witnessed the fishermen unloading vast hauls of lake herring, whitefish, sturgeon, and blue pike and would have scarcely imagined that in fifty short years the industry (and the very fish themselves) would be nearly extinct. Overfishing, pollution, and regulations ultimately conspired to make the proposition economically unfeasible. As of this writing, there is but one remaining commercial boat fishing from the Pennsylvania shore of Lake Erie.

|

THE WAR OF THE GAUGES At a point precisely in the middle of the nineteenth century, in 1851, Erie was finally chartered a city. It is an interesting point of demarcation, for one can look at the first half of the century and see a town inextricably tied to shipping; while the second half of the century would reveal a city seeking its fortunes in manufacturing. In many ways, of course, this was simply a duplication of what was happening in cities around the country (indeed, the world), but Erie could take a certain pride in their seamless, successful transition to a manufacturing economy.

Erie was, of course, aided greatly by its proximity to the coal fields of Pennsylvania and the Great Lakes region in general. In addition, it enjoyed the growth of a hardworking immigrant population and the entrepreneurship of several leading citizens. The primary industry in Erie was metalworking, and by 1890 fully 1 in 6 residents (pop: 40,000) were employed in this capacity. The multitude of iron and brass works produced engines, boilers, malleable castings, stoves, and heavy machinery.

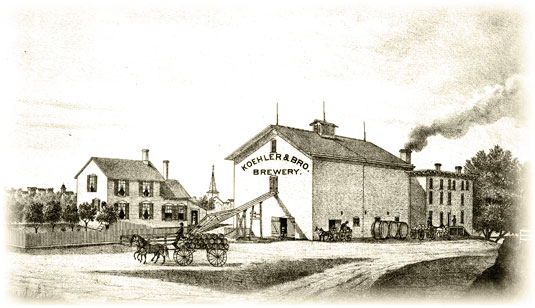

The immigrants brought with them a variety of skills, and these skills often lead to the creation of successful industries. For example, the city became a leading producer of pipe organs and pianos, due in large part to the musicality and craftsmanship of several German residents. The Koehler Brewing Company utilized old-world techniques to make its famous quaff, which it sold far and wide.

By 1895, when Erie celebrated its 100th birthday, one could walk down its paved streets and sidewalks knowing that they were in one of our country’s most thriving cities - a place where virtually any modern convenience could be made or purchased; a place where a multitude of nationalities coexisted en route to the American Dream; a place immensely prepared for the dawn of a new century. And a place quite unlike the foreboding shoreline that Colonel Seth Reed landed upon just one century before.

|

The Industrial Revolution  At a point precisely in the middle of the nineteenth century, in 1851, Erie was finally chartered a city. It is an interesting point of demarcation, for one can look at the first half of the century and see a town inextricably tied to shipping; while the second half of the century would reveal a city seeking its fortunes in manufacturing. In many ways, of course, this was simply a duplication of what was happening in cities around the country (indeed, the world), but Erie could take a certain pride in their seamless, successful transition to a manufacturing economy. At a point precisely in the middle of the nineteenth century, in 1851, Erie was finally chartered a city. It is an interesting point of demarcation, for one can look at the first half of the century and see a town inextricably tied to shipping; while the second half of the century would reveal a city seeking its fortunes in manufacturing. In many ways, of course, this was simply a duplication of what was happening in cities around the country (indeed, the world), but Erie could take a certain pride in their seamless, successful transition to a manufacturing economy.

Erie was, of course, aided greatly by its proximity to the coal fields of Pennsylvania and the Great Lakes region in general. In addition, it enjoyed the growth of a hardworking immigrant population and the entrepreneurship of several leading citizens. The primary industry in Erie was metalworking, and by 1890 fully 1 in 6 residents (pop: 40,000) were employed in this capacity. The multitude of iron and brass works produced engines, boilers, malleable castings, stoves, and heavy machinery.

The immigrants brought with them a variety of skills, and these skills often lead to the creation of successful industries. For example, the city became a leading producer of pipe organs and pianos, due in large part to the musicality and craftsmanship of several German residents. The Koehler Brewing Company utilized old-world techniques to make its famous quaff, which it sold far and wide.

By 1895, when Erie celebrated its 100th birthday, one could walk down its paved streets and sidewalks knowing that they were in one of our country’s most thriving cities - a place where virtually any modern convenience could be made or purchased; a place where a multitude of nationalities coexisted en route to the American Dream; a place immensely prepared for the dawn of a new century. And a place quite unlike the foreboding shoreline that Colonel Seth Reed landed upon just one century before.

|

|

|

|

A Product of Matthew D. Walker Publishing, LLC © 2025

A Product of Matthew D. Walker Publishing, LLC © 2025